Tutorial 2 - Memory Manipulation

Again, we are provided with a ELF32 binary. Let's run it!

./xor

Enter the password: 1234

Wrong!

Note: These exercises are purely didactic in nature and, therefore, not dangerous. However, binaries you encounter in real life can be very harmful to your device. Always try to avoid running them; if all other options are ruled out (static analysis, emulation), run them in a controlled environment.

Ah, it's asking us for a correct password. No doubt it lies somewhere hidden in the binary.

We can load it in radare2.

r2 -Ad xor

Notice the 'd' option, which specifies the fact that we will be doing some debugging and instruction tracing.

We can see a list of strings contained within this binary with 'iz' (info strings).

[0xf76e4d8b]> iz

vaddr=0x08048720 paddr=0x00000720 ordinal=000 sz=21 len=20 section=.rodata type=ascii string=Enter the password:

vaddr=0x08048735 paddr=0x00000735 ordinal=001 sz=5 len=4 section=.rodata type=ascii string=%32s

vaddr=0x0804873a paddr=0x0000073a ordinal=002 sz=7 len=6 section=.rodata type=ascii string=Wrong!

vaddr=0x08048741 paddr=0x00000741 ordinal=003 sz=13 len=12 section=.rodata type=ascii string=Good job! :)

Ah, no luck here. We were hoping to find the password kept in the .rodata section. But that's bad practice, isn't it?

We can list all of the strings contained in the binary, regardless of section, using the more verbose 'izz'.

[0xf76e4d8b]> izz

...

vaddr=0x0804850d paddr=0x0000050d ordinal=017 sz=6 len=5 section=.text type=ascii string=XZWh5

vaddr=0x08048574 paddr=0x00000574 ordinal=018 sz=5 len=4 section=.text type=ascii string=PTRh

vaddr=0x08048580 paddr=0x00000580 ordinal=019 sz=6 len=5 section=.text type=ascii string=\bQVhP

vaddr=0x080486e0 paddr=0x000006e0 ordinal=020 sz=5 len=4 section=.text type=ascii string=t$,U

vaddr=0x080486f7 paddr=0x000006f7 ordinal=021 sz=9 len=7 section=.text type=ascii string=\f[^_]Ív

...

Nothing here either, however we do find some interesting string snippets in the .text section.

Let's move forward a bit. We can continue execution until main is reached via dcu main (debugger continue until main).

[0xf77a2a90]> dcu main

Continue until 0x08048450

hit breakpoint at: 8048450

Debugging pid = 18388, tid = 1 now

[0x08048450]>

Now we can enter visual mode to get an idea of what's going on.

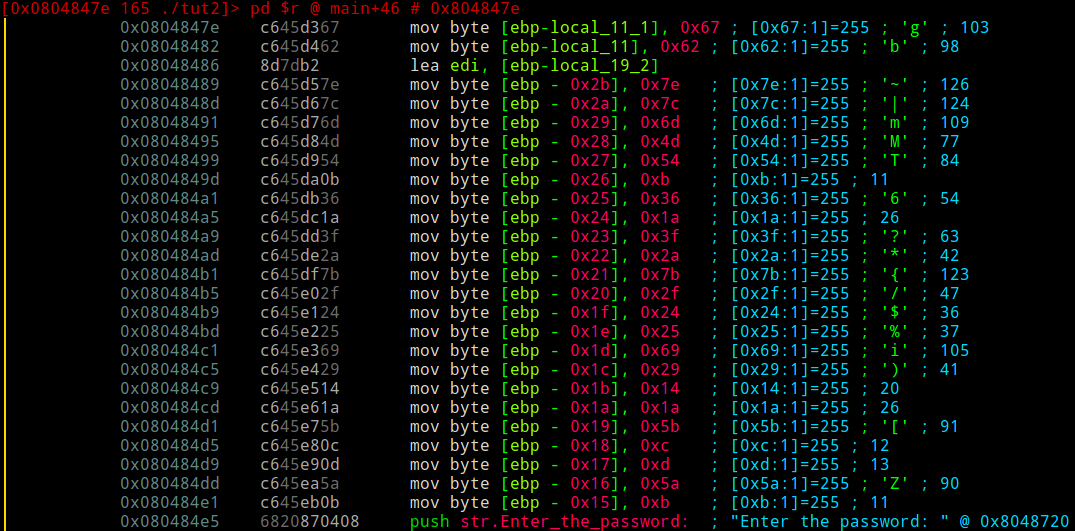

Holy smokes, that's a lot of copying onto the stack! This could be the required password in one form or another. Let's resume.

Note: We haven't executed anything by navigating with hjkl or the arrow keys. The program counter, eip, is still at the beginning of main. To move the screen back to eip at any time, press '.'.

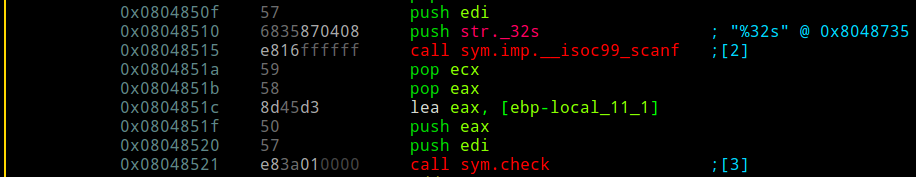

Ah, it seems that a 32 byte string is being read via scanf. edi will then point to our string. Soon after follows a call to sym.check, which verifies our input string against the string pointed at by eax.

Let's continue until we reach sym.check (q, then dcu sym.check). The program will ask for the password again. Since we don't know it yet, we'll input a bogus one once again.

[0x08048500]> dcu sym.check

Continue until 0x08048660

Enter the password: 1234

hit breakpoint at: 8048660

[0x08048660]>

We've now reached the sym.check function. Let's inspect its code.

[0x08048660]> pdf

╒ (fcn) sym.check 58

│ ; CALL XREF from 0x08048521 (sym.check)

│ ;-- eip:

│ 0x08048660 83ec0c sub esp, 0xc

│ 0x08048663 b82a000000 mov eax, 0x2a ; '*' ; 42

│ 0x08048668 8b4c2410 mov ecx, dword [esp + 0x10] ; [0x10:4]=-1 ; 16

│ 0x0804866c 89ca mov edx, ecx

│ 0x0804866e 6690 nop

│ ┌─> 0x08048670 3002 xor byte [edx], al

│ │ 0x08048672 83c003 add eax, 3

│ │ 0x08048675 83c201 add edx, 1

│ │ 0x08048678 3d8a000000 cmp eax, 0x8a ; 138

│ └─< 0x0804867d 75f1 jne 0x8048670

│ 0x0804867f 83ec04 sub esp, 4

│ 0x08048682 6a20 push 0x20 ; 32

│ 0x08048684 51 push ecx

│ 0x08048685 ff742420 push dword [esp + 0x20]

│ 0x08048689 e8b2fdffff call sym.imp.strncmp

│ 0x0804868e 85c0 test eax, eax

│ 0x08048690 0f94c0 sete al

│ 0x08048693 83c41c add esp, 0x1c

│ 0x08048696 0fb6c0 movzx eax, al

╘ 0x08048699 c3 ret

This code should be fairly easy to understand. Our input gets copied from the stack ([esp + 0x10]) into ecx, and edx.

The string address is also moved in edx. Then, within a loop, each byte of the input string gets XOR'ed with al, which starts at 42 and gets incremented by 3 at every iteration, until reaching an upper bound of 138 (which is 42 + 32*3).

Now edx points to the end of our string. Luckily, ecx still points to the starting address. We can then see that ecx and the reference string (which was in eax before calling sym.check) are compared. Let's see what the two strings look like.

[0x08048660]> ps @ eax

gb~|mMT\x0b6\x1a?*{/$%i)\x14\x1a[\x0c\x0dZ\x0b*

J\x19\xe9\xb3\xda

[0x08048660]> ps @ edi

1234

Reminder: Every instruction in radare, by default, is executed with respect to the current offset within the file (the one indicated on the left). If you want to execute something at a different point, there are two options:

- Seek to that point, execute, seek back.

- Supply a relative offset to the instruction via the @ symbol. This is the same as (1), but in a more compact, comprehensive form.

So, for example, if you wish to view the main function while you are somewhere else, you can type pdf @ main. You can use any flag or address as relative offsets.

What do we have so far? Our input string gets mangled up slightly by the check function and then compared with the reference string. We can reverse engineer this simple algorithm inside radare.

We are going to have to XOR the string pointed at by eax with 42, 45, 48 etc. in order to recover the password.

Let's first generate the pattern with woe.

[0x08048660]> woe 42 3 @ edi!32

from 42 to 255 step 3 size 1

[0x08048660]> ps @ edi!32

*-0369<?BEHKNQTWZ]`cfilorux{~\x81\x84\x87

[0x08048660]> p8 32 @ edi

2a2d303336393c3f4245484b4e5154575a5d606366696c6f7275787b7e818487

Don't panic. Let's examine these instructions in a systematic manner. 'w' is used for writing things in memory. 'o' specifies that an operation will be carried out when writing. 'e' stands for sequence

The sequence starts with the value 42 and is incremented by 3 at each position, similar to what the sym.check function is using to XOR our input. Now we need to write this sequence somewhere. Since edi is garbage anyways, we can write at whatever edi is pointing at. The exclamation mark is a size specifier (up to what offset to write). Otherwise, the write operation will continuously write from edi onwards. We risk overwriting valuable data.

So the code above places the sequence of values 42, 45, 48, etc. from edi till edi+32 (address-wise). If we do a quick conversion, we notice that 0x2a == 42. If you are lazy nimble, you can use radare to do these conversions for you.

[0x08048660]> ? 0x2a

42 0x2a 052 42 0000:002a 42 "*" 00101010 42.0 0.000000f 0.000000

The first part is done, we have our string. Now we need to XOR this string with the reference string to get the original password. Don't start scripting just yet, we can still use radare to do this.

If we look around wo?, we can see that wox might be what we're looking for. But the only example is one in which a single value is XORed with (assumed) multiple values.

If you remember from our previous tutorial where we used backticks (`) like in bash to nest a command within another command and expand its output upon evaluation, we can do something similar here.

Again, we'll construct it step by step. We're trying to get the following:

[0x08048660]> wox <my_pattern> @ eax!32

This would XOR my_pattern from eax to eax+32. We saw earlier that we can get a continuous hex string via the following:

[0x08048660]> p8 32 @ edi

2a2d303336393c3f4245484b4e5154575a5d606366696c6f7275787b7e818487

Now we can surround the expression via backticks (or just copy the value directly; but we know better, right?)

[0x08048660]> ps @ eax

gb~|mMT\x0b6\x1a?*{/$%i)\x14\x1a[\x0c\x0dZ\x0b*

J\x19\xe9\xb3\xda

[0x08048660]> wox `p8 32 @ edi` @ eax!32

[0x08048660]> ps @ eax

MONO[th4t_wa5~pr3tty=ea5y_r1gh7]

We got a string which doesn't look as random anymore. Let's test it.

./xor

Enter the password: MONO[th4t_wa5~pr3tty=ea5y_r1gh7]

Good job! :)